Chances are that if you live in the Bronx today, you spend most of your time working in a job that makes more money for someone else than it does for you, and living in a home that you pay someone else to live in. The main message we hear is that the way to success out of these situations is to become the business owner or become the property owner. While this current economic system may work for some, we can see by the circumstances today in the Bronx that it is not working for our communities.

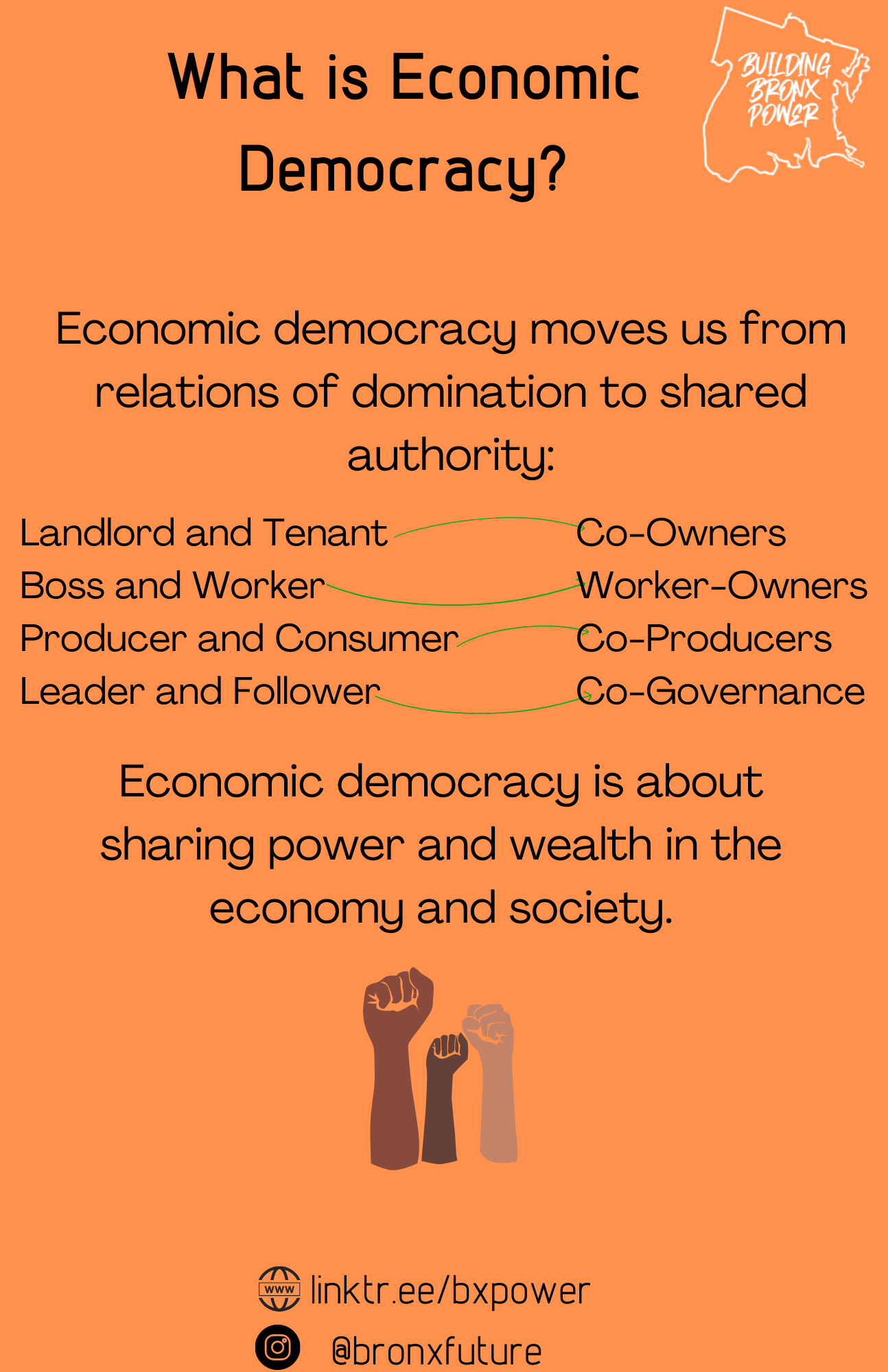

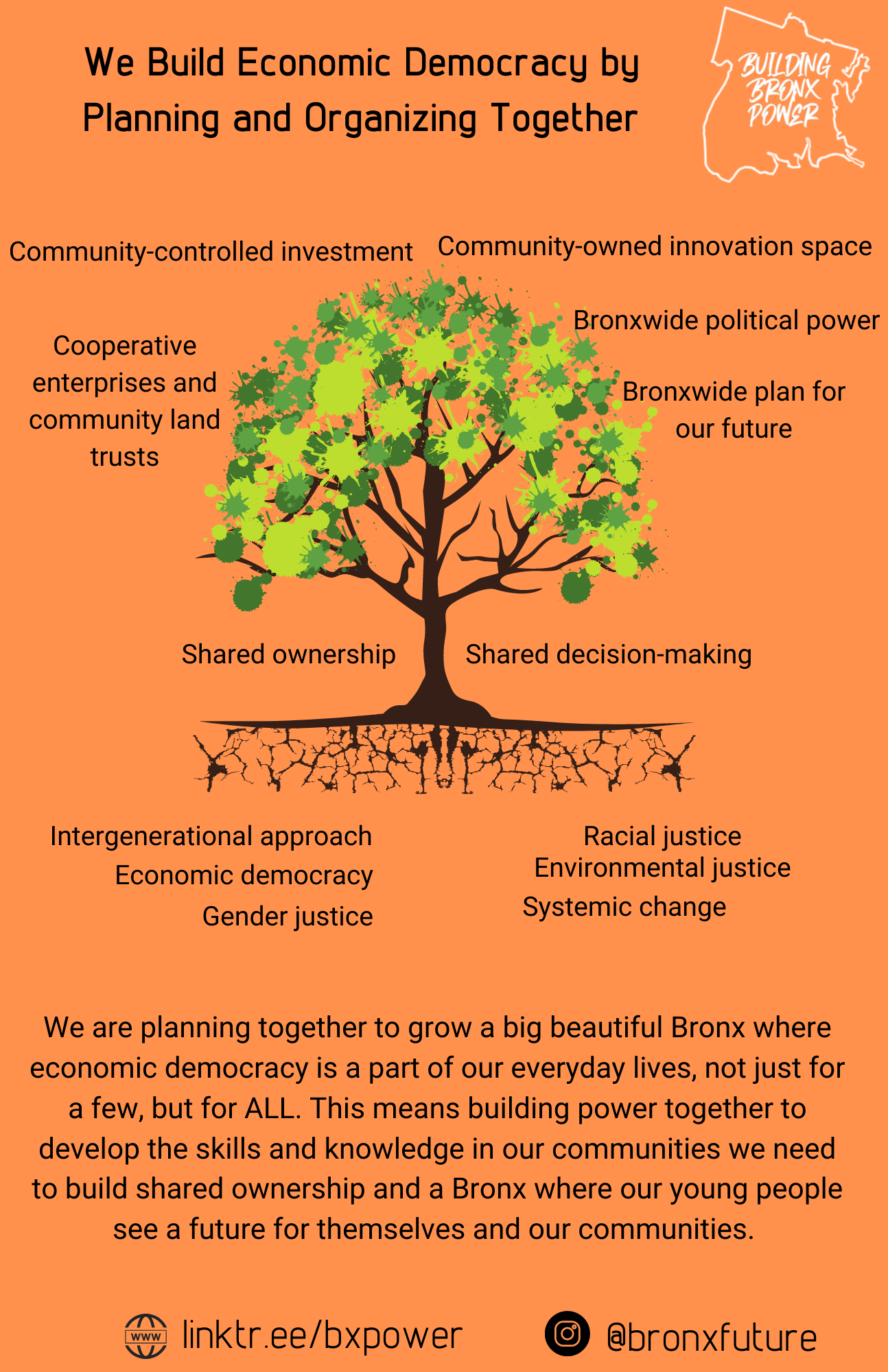

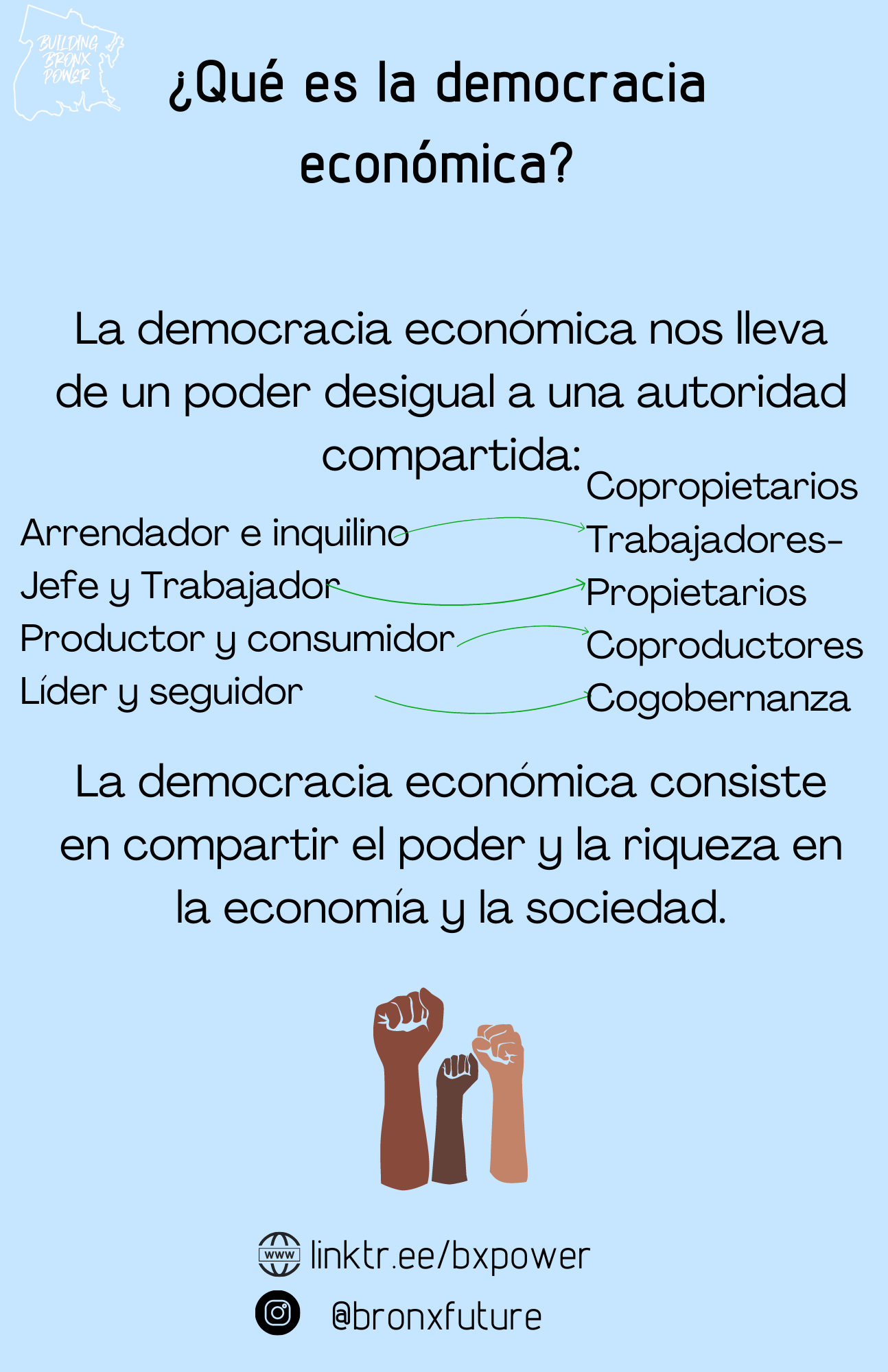

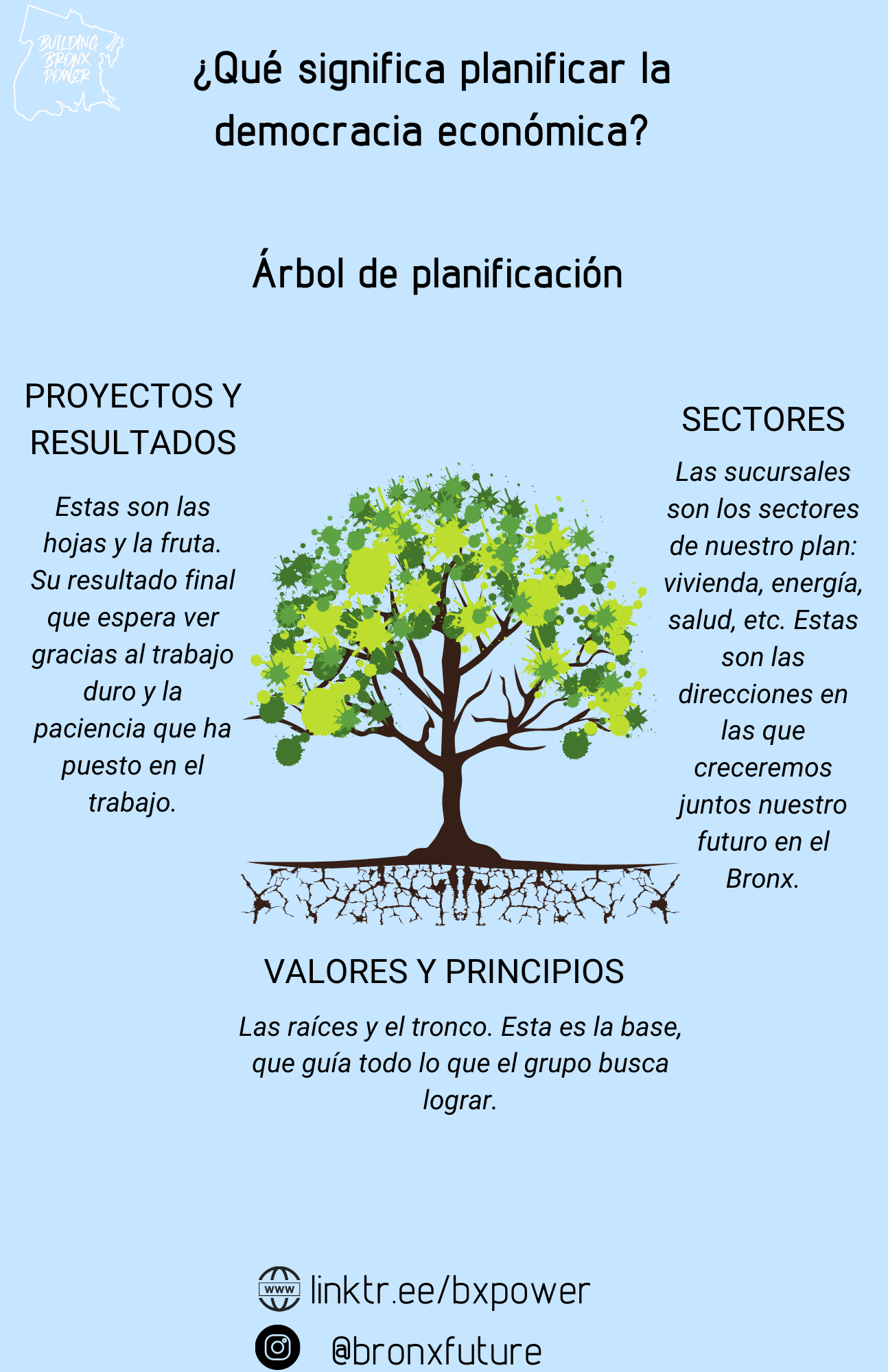

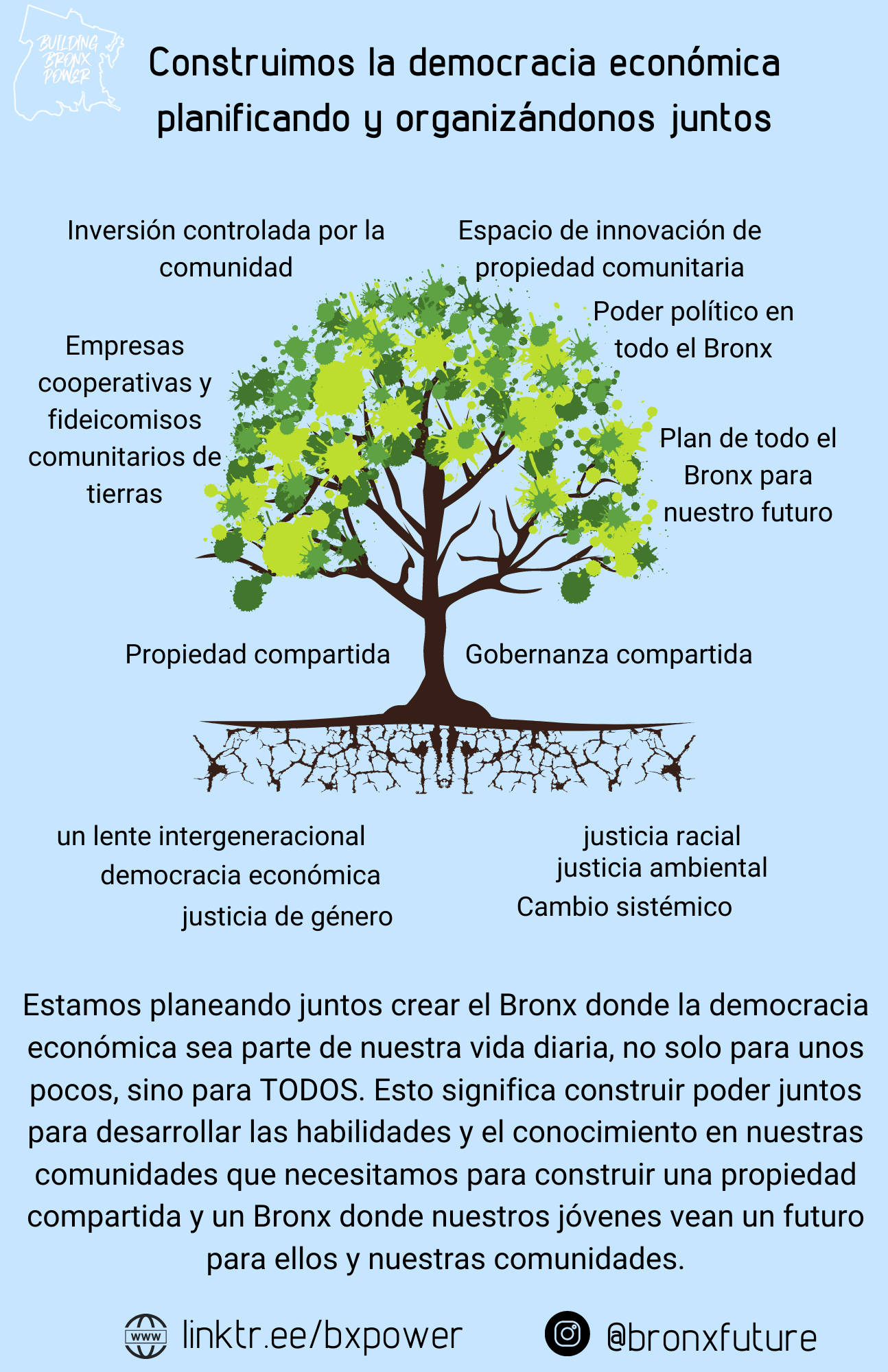

We believe our economy can and must work differently. Economic democracy is a system where people share ownership and decision making over the power and resources in their communities. Rather than profit and pure self-interest, it is grounded in values of solidarity, cooperation, democracy, and sustainability.

Where economic democracy exists at substantial scales in urban regions, we see significantly reduced inequality and greater well-being for all, especially working people. Economic democracy reduces inequality and increases the shared wealth we have in our communities, not just creating huge amounts of wealth for small numbers of people.

Economic democracy does not just mean creating more programs or more access or “input” and participation. It means real partnership and shared power, control, and benefit for everyday people in the things that matter in our lives.

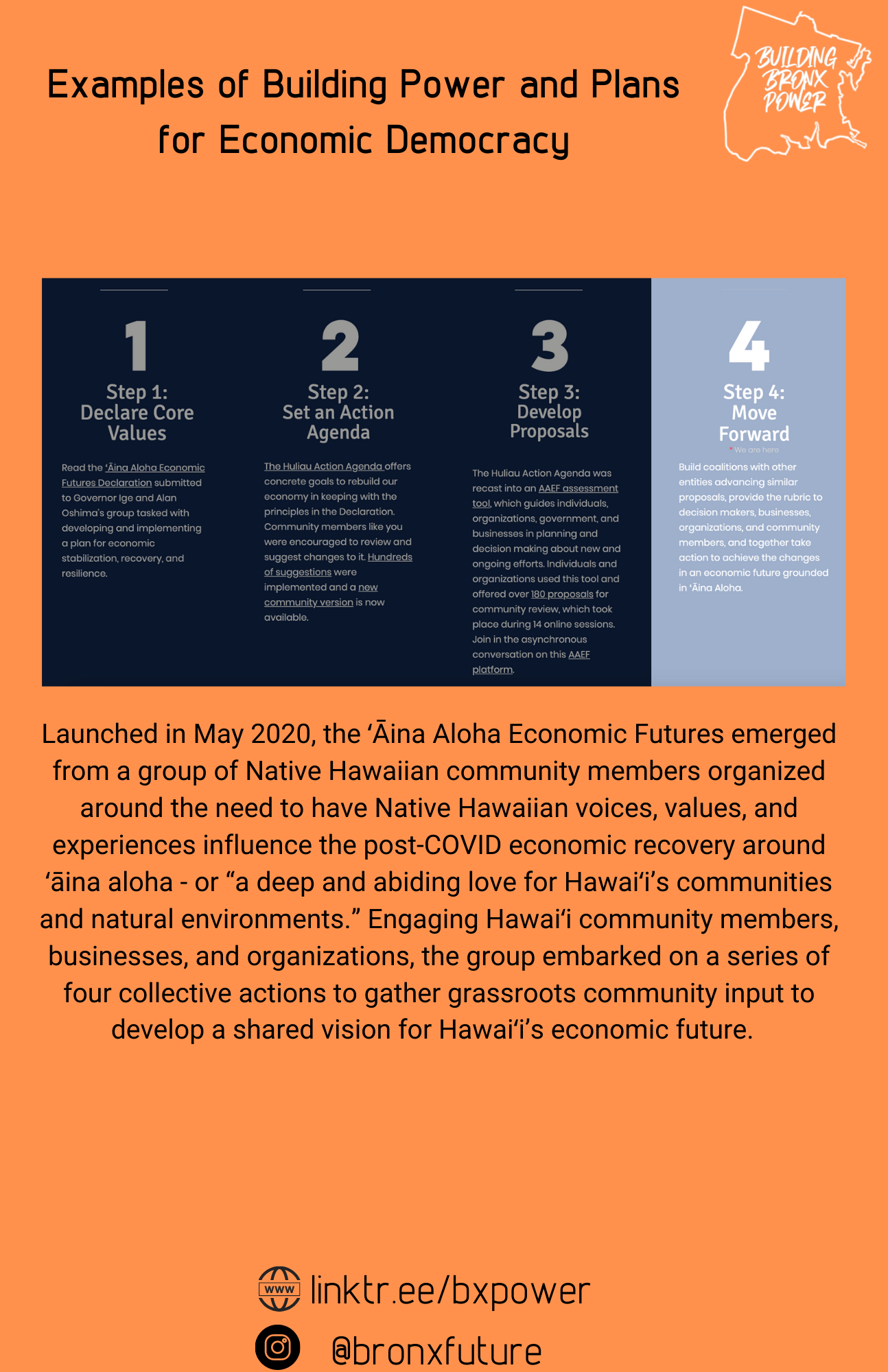

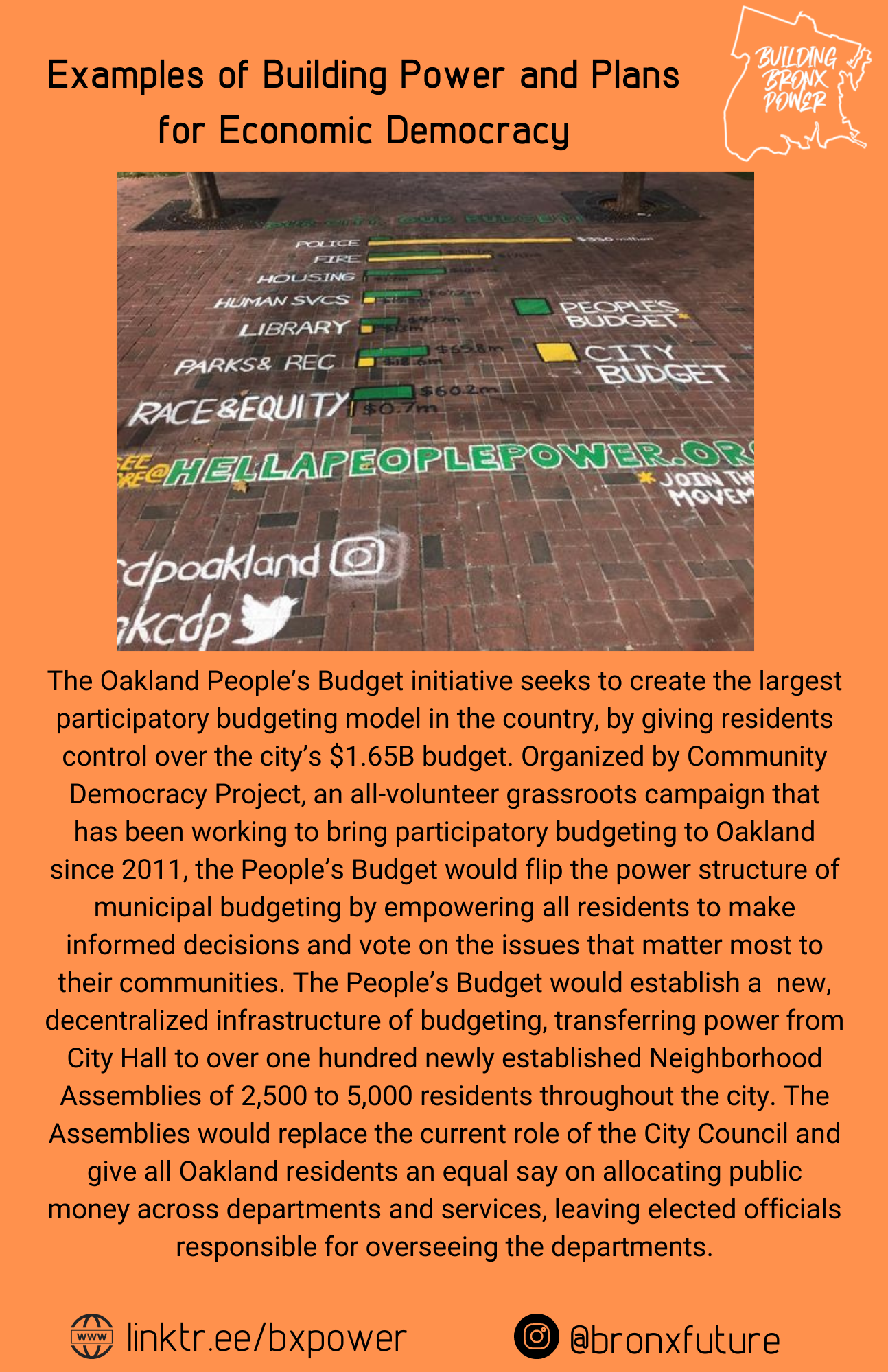

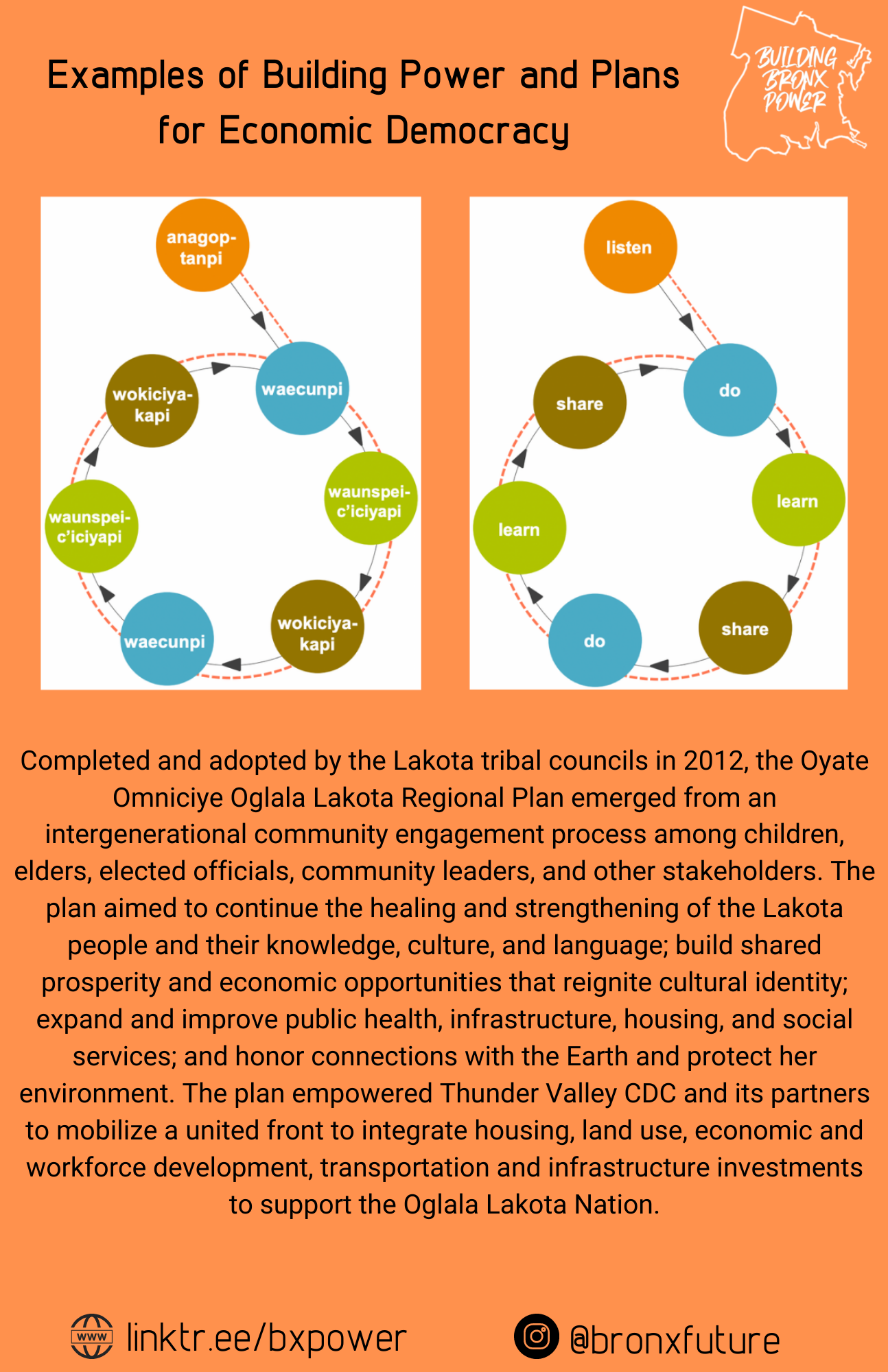

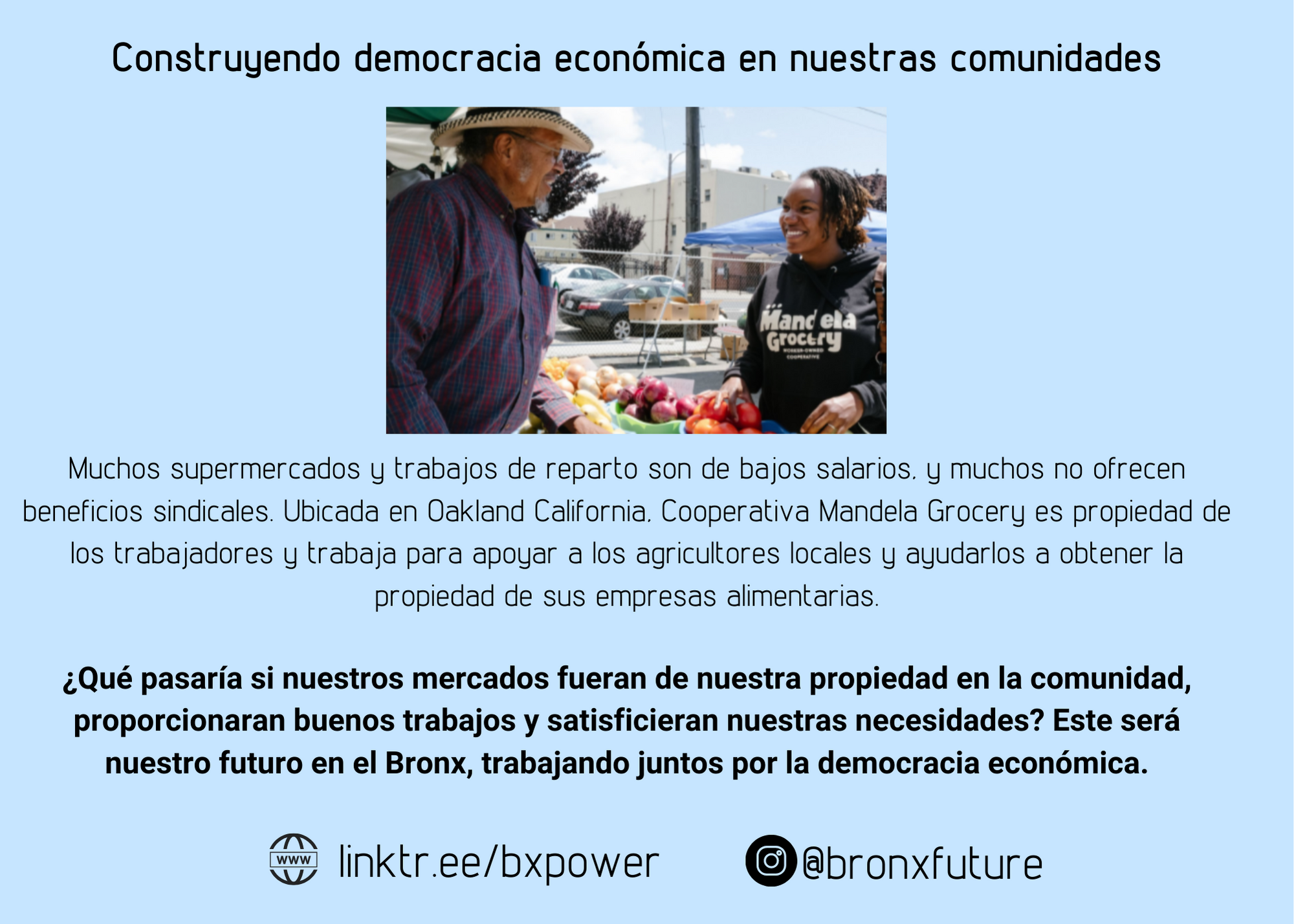

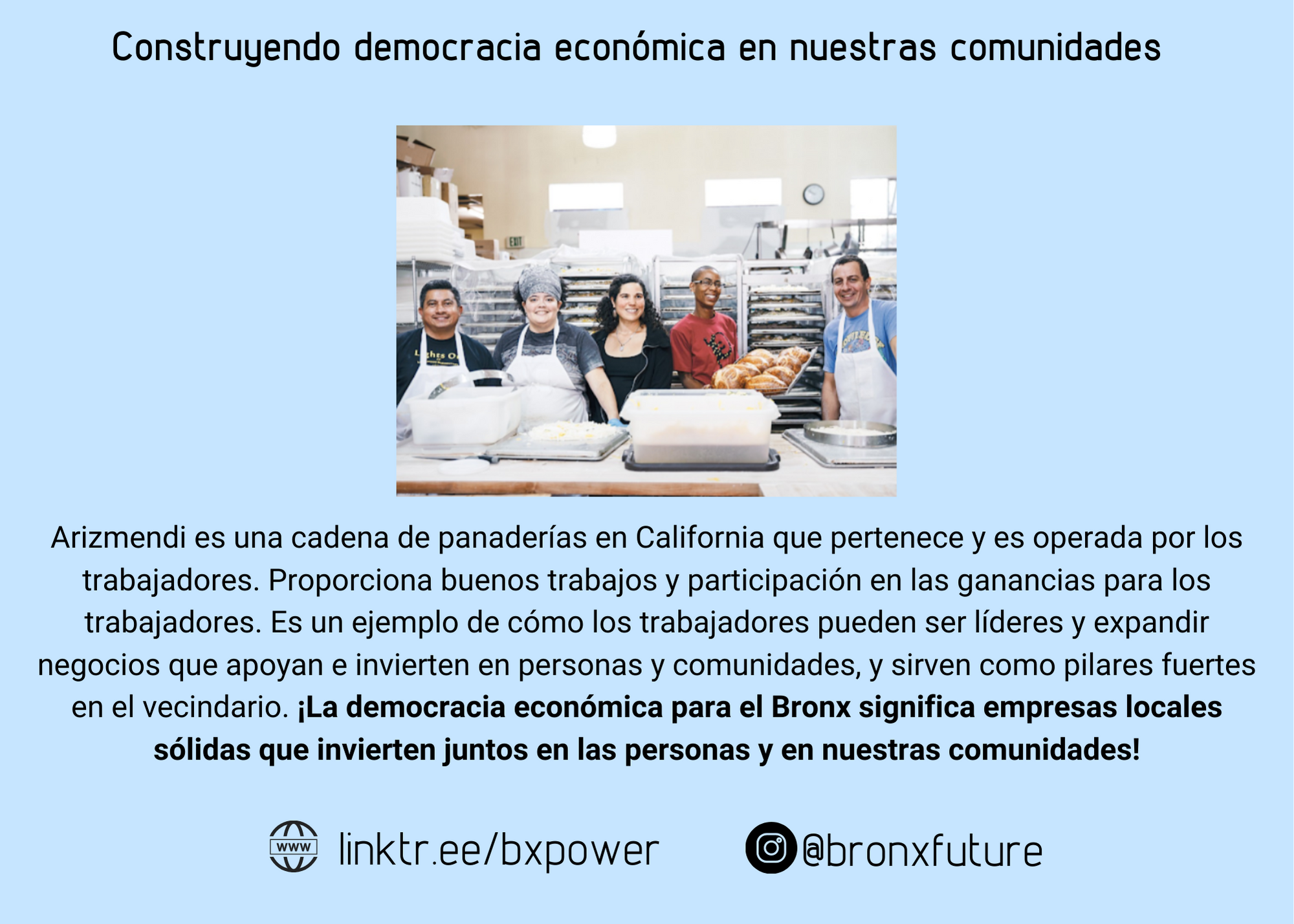

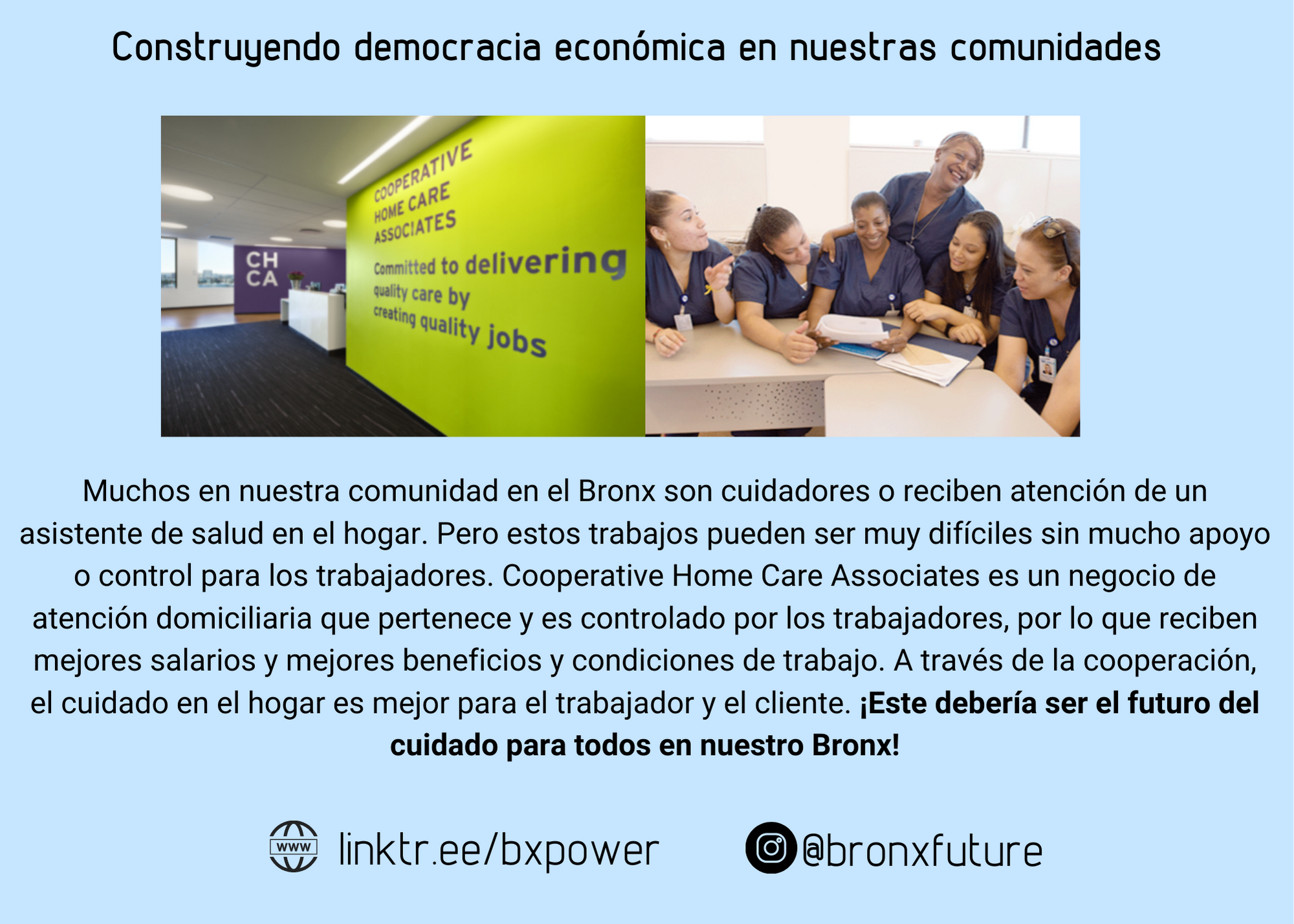

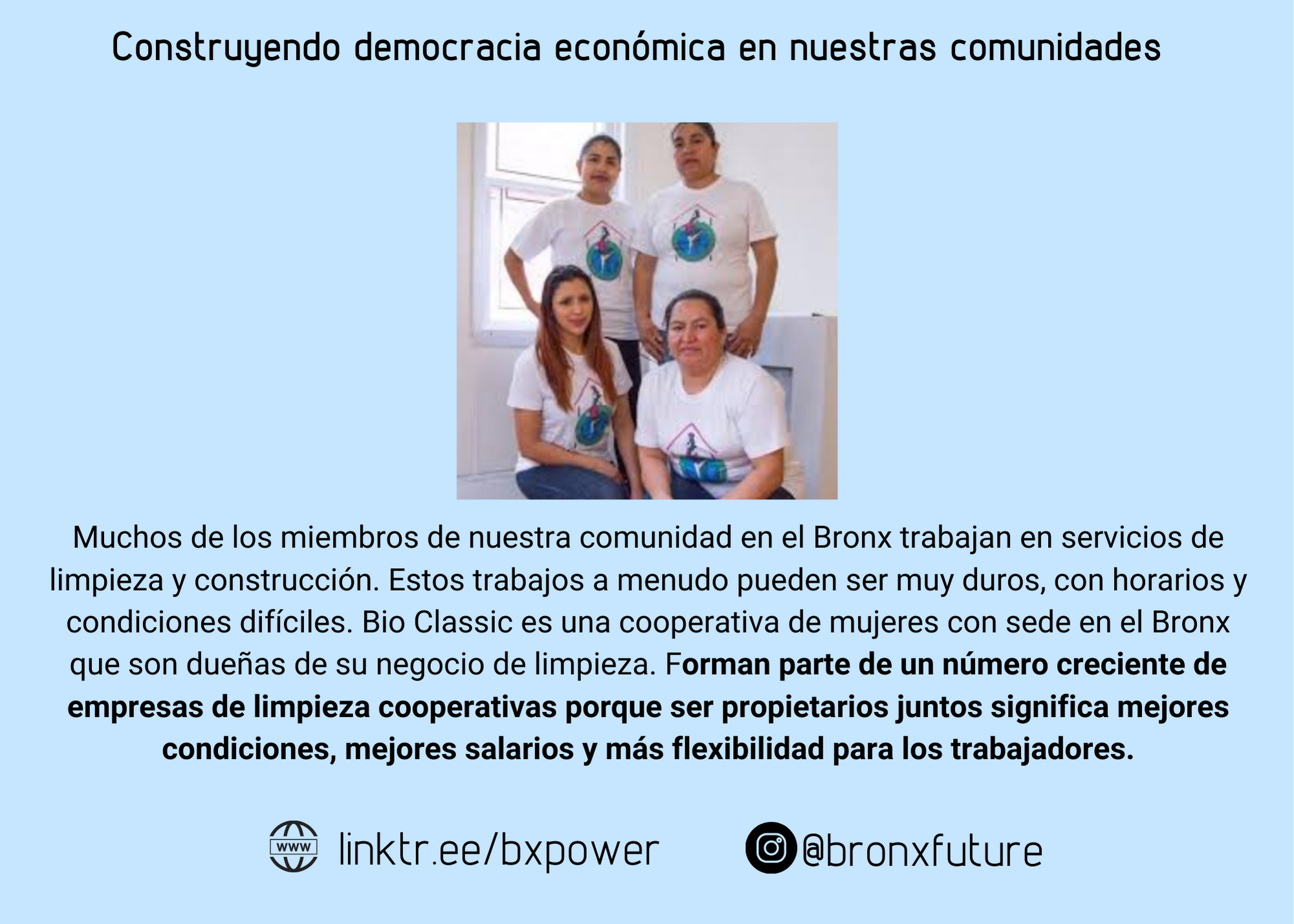

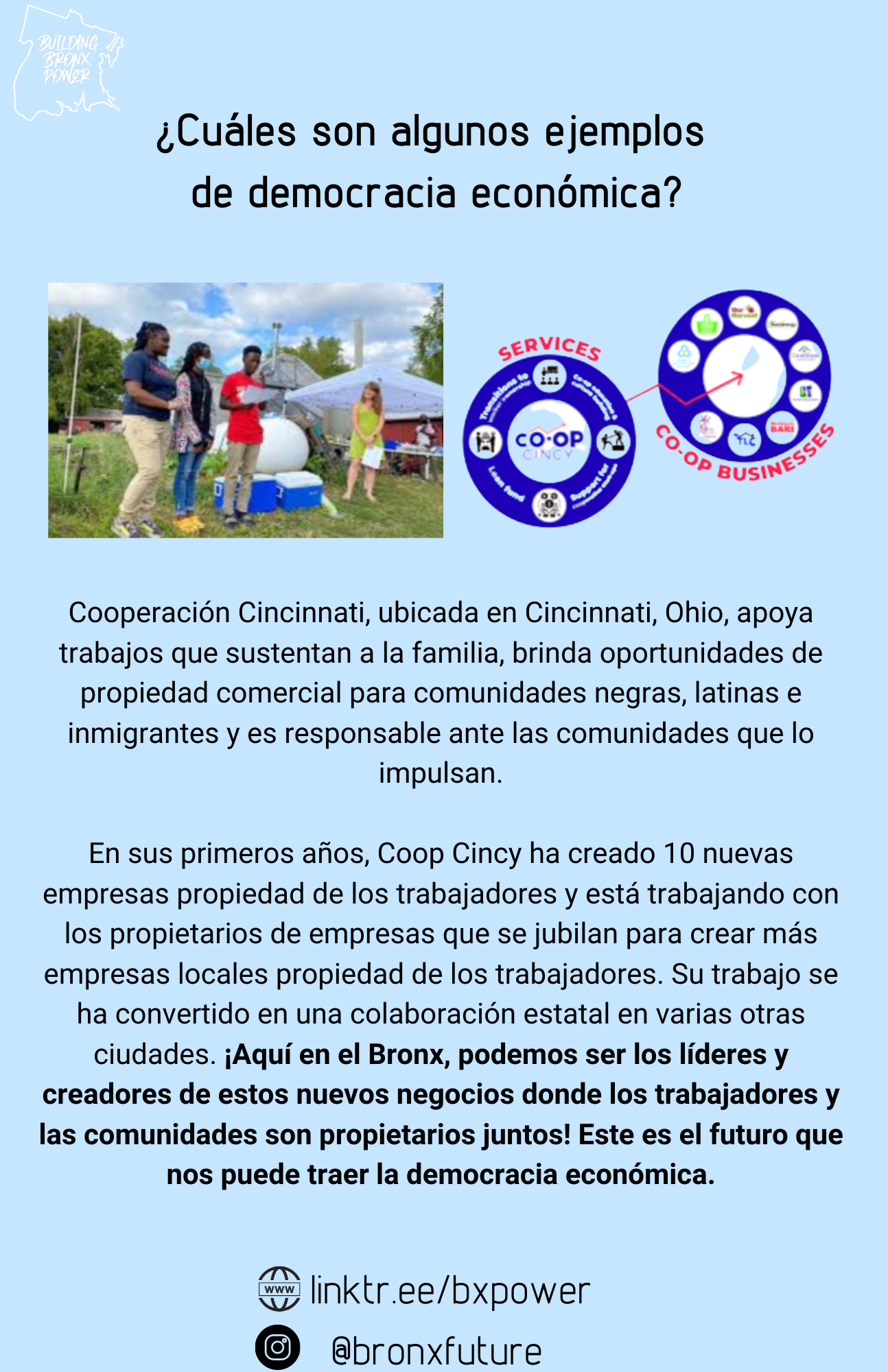

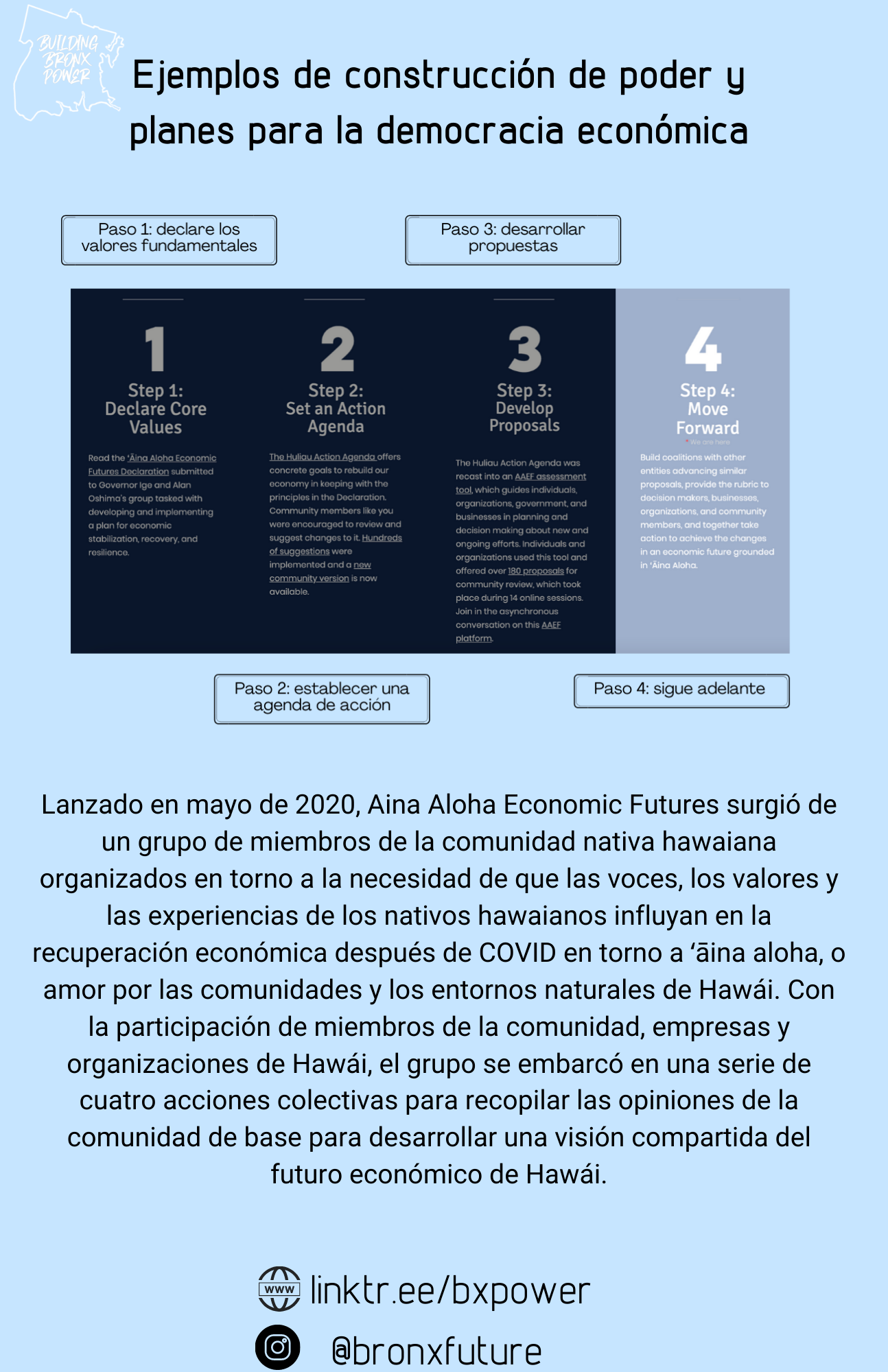

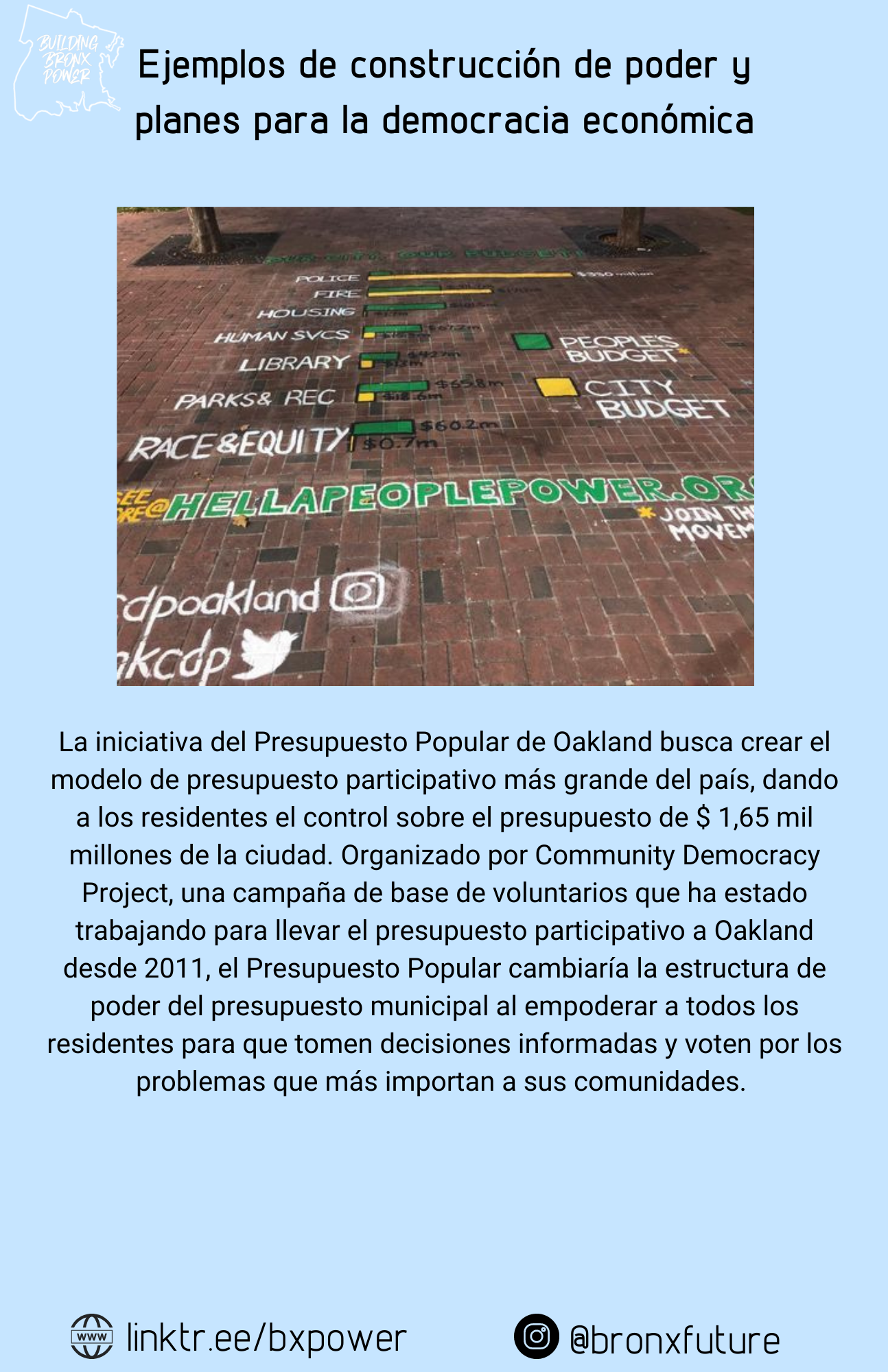

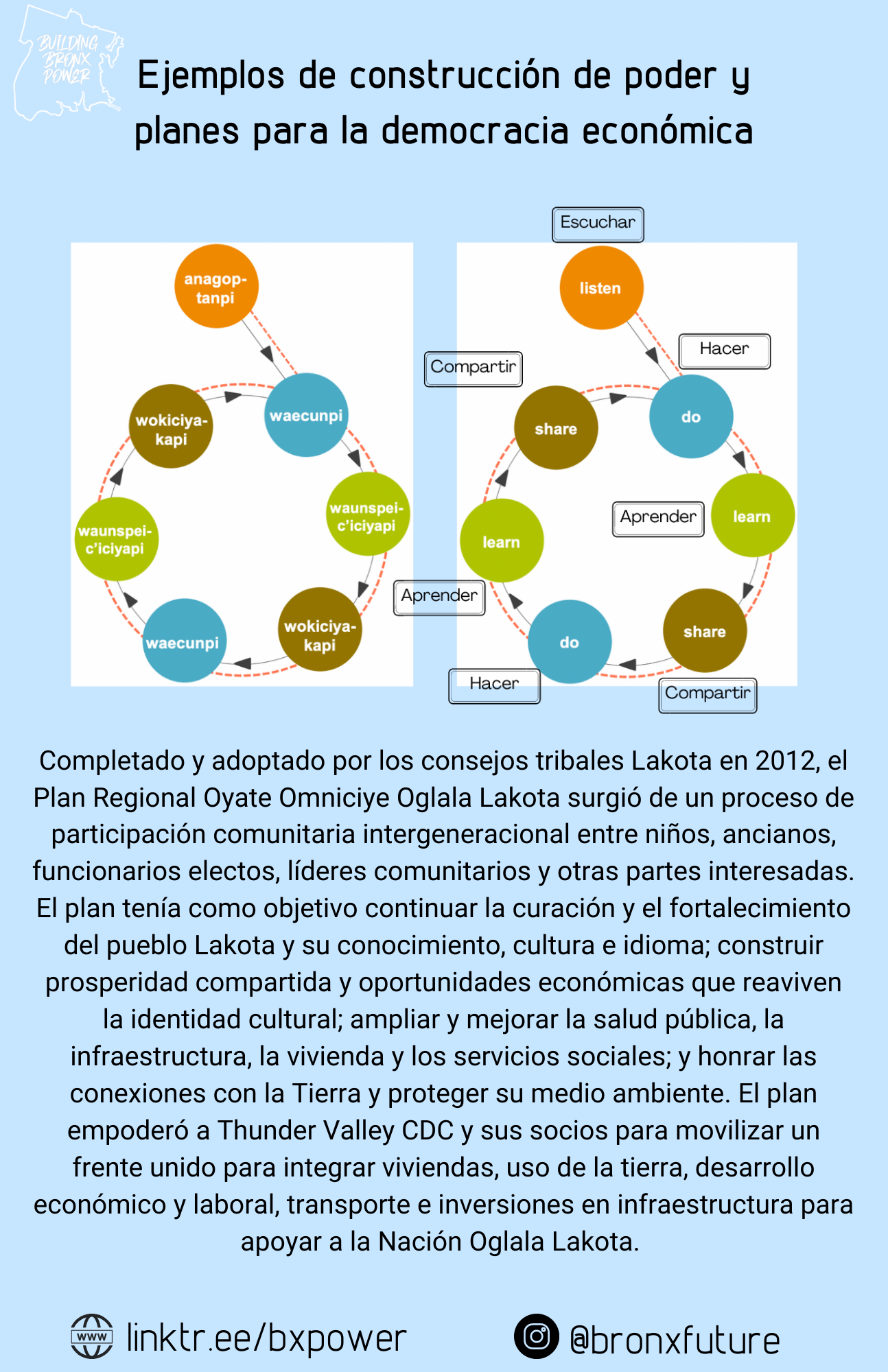

What can economic democracy look like in practice? We created some of these case studies and materials to help acquaint people with how economic democracy offers a concrete way for us to develop our neighborhoods together, and an alternative development model for our city and region that creates shared economic prosperity.

Download the above as PDFs

Handout Cards - English | Handout Cards - Español| Our Bronx Our Plans - English | Nuestro Bronx Nuestros Planes - Español

Economic democracy, to me, means...ownership. By ownership, I mean the physical ownership, but I also mean the governance and the sustainability of it...It is about an example for what is possible... It’s a whole different way to organize people and train them to work together to build something.

—Danny

I really recommend that anybody in the community should really learn about...where the money is so we can...strategize and figure out how to get this money back into the community and make sure it stays.

—Akilah

As we’re elevating the voices of young people and the struggles that they’re going through right now, we [also] want to develop young people to take on different positions within decision-making spaces, how do we develop young people to take on these positions in the Department of Education, where they’re making decisions for other young people that are actually grounded in the young people’s vision?

—Crystal

Frequently Asked Questions

Is economic democracy capitalism or socialism?

It depends on what you mean by capitalism and socialism. Economic democracy as a framework has been championed and disparaged by capitalists and socialists alike throughout history. So this is an important question and debate. But if the question is, does BCDI want the economy to be owned and controlled by the federal government, the answer is definitely no.

There are quite a few frames for thinking about visions for a better world, from the “Pluralist Commonwealth” to the Solidarity Economy, as well as economic democracy. The kinds of institutions, policies, and cultures that develop around these values have taken many different shapes throughout history: cooperatives have been used for centuries in housing, finance, the workplace, and food and land ownership. But economic democracy isn’t only about cooperative ownership either, and can involve public ownership and management, community control, and other hybrid combinations of ownership and governance. The key is that the values of democratic governance and shared control and/or ownership are fundamental across all of these histories. This is where we at BCDI locate our core understanding and vision for economic democracy as well.

Then isn't this just capitalism?

We don’t think so, but, like the above question, it depends what you mean when you say capitalism. Our current economic system is designed to reward certain individuals at the cost of others. As such, it is fundamentally and structurally incapable of delivering the kind of equity, ownership and control, and justice that we envision. Thus, we do not believe only in an “inclusive” approach that seeks to bring access and opportunities to participate in the current economic system. Nor are we working to enrich just a few Bronxites who can then “give back” to the rest of the Bronx with a few jobs or through philanthropy. This has typically been called “black capitalism” and while there are some useful elements to this, it is not our vision or strategy for economic democracy or for the Bronx.

Inclusion for marginalized people and communities into our current economic system is akin to being invited to a dinner where everyone else is already eating and on their second helping. We are not working for just a plate or seat at that table. We are cooking in a different kitchen and building new table. We are working for new and different institutions that broaden and democratize ownership and innovation, and proliferate and deepen the practice of democracy in our daily lives.

Economic democracy ecosystems can exist within capitalist or socialist societies. Note that even within a capitalist system, not all relationships or exchanges are subject to capitalism’s rules. Think about how you interact with family members or close friends; rarely are you thinking about the dollar amount of the favors you give or ask of them. Similarly, economic democracy can exist within larger systems that are capitalist or socialist.

Can it work in a diverse place like the Bronx or New York City?

Some examples of economic democracy do exist in ethnically homogeneous contexts, for instance the Basque Region of Spain, in Japan, or Québec, Canada. While ethnic solidarity may facilitate some useful forms of social bonding and cohesion (and some harmful ones too) for participatory governance, it is possible to build shared values and identities with diverse groups as well. In our planning and visioning, we were inspired by the example of Market Creek Plaza in San Diego, which utilized aspects of community ownership and control in a multi-racial community. Community organizing, leadership development, and education become especially important in this context, in order to build a shared sense of purpose and deep, trusting relationships. Identity and community are not fixed, but can be shaped over time through shared experiences and values, not only ethnicity or religion, and so on.

In fact, BCDI sees diversity as a strength, not a weakness or a barrier to economic democracy. The diversity of the Bronx will make our version of economic democracy and democratic control more adaptable, resilient, and innovative in the long-term, and it will arise from, and belong to, all of the countries and languages and faith traditions and identities that exist here. This speaks to the enduring need for cultural and social dimensions to organizing for economic transformation, so that values of cooperation and democracy, of shared responsibility for shared benefits, are reinforced throughout our lives.

Isn’t this a white people thing?

Hell no. Collective ownership and collective governance are longstanding historical responses to economic, racial, and colonial violence and oppression among indigenous and Black people. At BCDI, we draw inspiration from regional economies grounded in freedom struggles from around the world, such as:

The Pacific Coast Region of Colombia, where Afro-Colombian communities won the right, by law, to democratically control their land with community councils.

The Mondragón network of cooperative enterprises and institutions in the Basque region of Spain, where the Basque had faced ethnic cleansing and terrorism from Franco’s dictatorship in Spain. The bombing of the Basque city of Guernica inspired Picasso’s famous anti-war painting.

The Young Negroes’ Cooperative League, led by Ella Baker in the 1930s, was a national network of black youth to pool capital and start cooperative enterprises during the depression. This and many other stories of economic cooperation are covered in Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s book, Collective Courage, in Barbara Ransby’s Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, and more.

The New Communities Land Trust in the US South, usually considered the first Community Land Trust in the United States. It was an outgrowth of civil rights struggle, and was led by organizers from the civil rights organization SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee).

Is this the same thing as worker cooperatives and employee ownership?

Worker cooperatives, where workers own and democratically run the company with one worker, one vote, and majority employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) are two examples of economic democracy, because they apply principles of democratic practice to one part of the economy: the workplace or the firm. But that’s not all economic democracy means. Economic democracy can also extend to housing, land, food, education, and nearly every part of the economy and our lives. Additionally, employee stock option plans (ESOPs), the most common form of employee ownership in the US, typically provide ownership but not decision-making control. Without collective governance, ESOPs are just profit sharing, and do not meet our criteria for economic democracy.

Lastly, we have to separate form (cooperative or employee ownership) from values. For instance, in New York City, there are thousands of cooperatively owned apartment buildings; however, these are often some of the most expensive and exclusive buildings in the city. Cooperative ownership without shared values of solidarity and social justice, or those that do not strive to uphold the international cooperative principles, do not achieve what we mean by economic democracy.

Why is cooperative in your name then?

The cooperative in Bronx Cooperative Development Initiative refers to economic cooperation in the broadest sense, as this is a core requirement of economic democracy. We are not using it to refer specifically to worker cooperatives (which are often also confusingly just called “cooperatives”). We understand this can be confusing.

I noticed you use the word infrastructure a lot. Are you fixing the subway?

We wish, but no. When we say infrastructure, we mean social infrastructure, like the education system, mass media, and political institutions. As with the kinds of infrastructure we are used to thinking about, like internet cables and power lines and water pipes, our social infrastructure is often invisible but serves critical functions for reinforcing mainstream values and assumptions in society. In all areas of our lives—jobs and businesses, civic engagement, education, health, housing—we rely on social infrastructure. However, currently, almost none of these programs or institutions operate with a framework of economic democracy. We are working to change those existing institutions and to build new ones that do.

This sounds really expensive. Who pays for this? Are you going to raise my taxes or seize my private property?

It is expensive! And we need your support. If you are able to contribute to creating a more equitable, sustainable, and democratic Bronx economy, please consider making a donation. Outside of individual contributions, we have philanthropic and public-sector grants that support our work, and we are beginning to generate independent revenue through the operations of some of our projects.